Why Sorghum?

By Brent Bean, Ph.D., Sorghum Checkoff Agronomist

Many growers will be glad to see 2019 behind them. To say 2019 was a stressful year is an understatement. Weather conditions were simply not conducive for crop production in many regions of the country. However, grain sorghum actually had a decent year compared to some of the other crops. Its ability to withstand short periods of drought and high temperatures allowed the crop to produce a good yield across many areas. The final average expected yield across the U.S. will be around 76 bushels per acre, which is just below the record set in 2016 at 77.9 bushels per acre. This number is a testament to better hybrids being planted today and implementation of better management practices by growers.

Grain sorghum will respond to favorable growing conditions like other crops, but when conditions are less than ideal, sorghum tends to stand out by producing sustainable yields in tough environments.

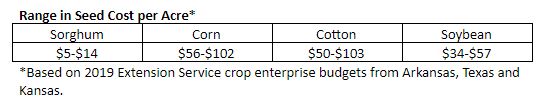

In an environment with low commodity prices, input costs must be considered and minimized when possible. The cost of growing sorghum is less than other major commodities, and lower costs begin with seed costs. The cost of seed varies considerably depending on the crop, seeding rate, traits and treatments applied to the seed. The table below reflects the range in seed cost per acre for dryland production of various crops.

High infestation levels and wide distribution of the sugarcane aphid in 2015 caused some growers to move away from sorghum. Since then, tolerant hybrids are now being planted in those areas most at risk from sugarcane aphid. Additionally, nature has adjusted to the presence of the aphid as beneficial insects have adapted to the new food source. As a result, most fields do not have to be treated with an insecticide, and when they do, one application is generally sufficient for season-long control.

The rotational benefits of sorghum with other crops should be an important consideration. Cotton yields are often higher following sorghum, sometimes by as much as 20 percent. Sorghum breaks up soil disease cycles such as verticillium wilt, and crop residue the following year increases soil moisture storage and protects emerging cotton from wind damage. By splitting an irrigated field between cotton and sorghum, water can often be concentrated on each crop during their critical growth stages. In the years where irrigation water is in greater demand than anticipated, growers can take comfort in sorghum’s ability to tolerate short periods of drought.

Higher soybean yields following sorghum are attributed to less disease, nematode and insect pests. Sorghum is a non-host plant to the soybean cyst, root knot and reniform nematode species.

Growers are often surprised to learn that corn yields are often higher following sorghum. A five year Kansas study showed an 8.4 percent yield increase when corn followed sorghum compared to continuous corn. Splitting an irrigated field with corn and sorghum also has its advantages. Irrigation water can be concentrated on corn at critical growth stages while supplementing the more drought tolerant sorghum crop when water is available.

We all hope for better weather conditions for crops in 2020. However, regardless of weather conditions, consider sorghum in your crop rotation. With sorghum’s input costs, tolerance to short periods of drought and heat, as well as it’s rotational benefits to other crops it has many benefits to offer growers. For more information on using sorghum in different cropping systems visit the Sorghum Checkoff website, sorghumcheckoff.com.