Planting, Row Spacing and Seeding Rate

Planting Date

Optimum planting dates are based on soil temperature, the timing of seasonal rainfall, daily maximum temperatures, risk of insect infestation and length of the growing season.

One of the first considerations for early planting should be soil temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower the sorghum will germinate and emerge. Most agronomists suggest waiting to plant sorghum until the minimum daily soil temperature is 60 degrees, and the forecast for the next 10 days is for high temperatures. The soil temperature can probably be a little lower than 60 degrees if the near-term forecast is for higher temperatures.

Keep in mind that how fast a sorghum plant develops is directly related to daily temperature or heat units. Early planting can delay the time when sorghum reaches the flowering stage anywhere from 7-25 days, depending on weather conditions and, to a lesser extent, the specific hybrid. If very early planting is a goal, check with seed companies for a hybrid that has cold tolerance. These hybrids will not experience as much of a delay due to lower temperatures.

Typically, one of the advantages of early planting is reducing the risk of insect damage. In most regions, headworms and midge issues are much less likely with early planting. From a sugarcane aphid management standpoint, this is important because many of the insecticides used for these two pests will cause sugarcane aphid populations to flare.

Late Planting Or Double Cropping

Growers often use grain sorghum as a double-crop behind wheat or a failed spring crop because sorghum has a relatively low input cost and can produce good yields with favorable late-season weather conditions. However, grain sorghum yields are much less consistent or predictable with late planting dates.

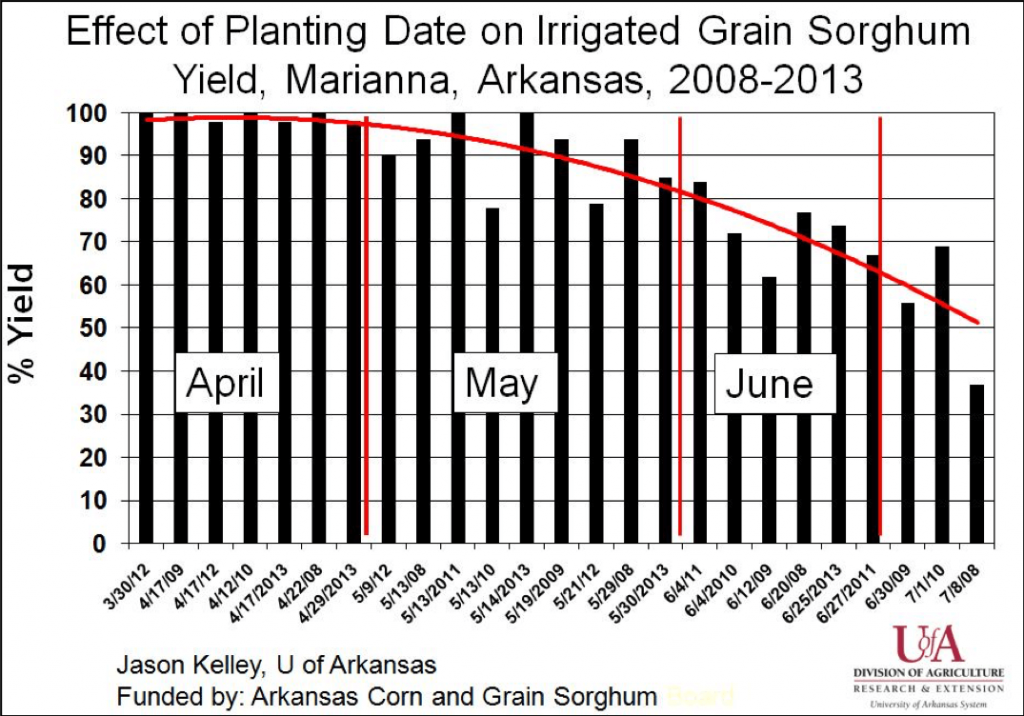

Researchers have conducted many planting date studies over the years where the results have been strongly influenced by local conditions during the time frame of the trial. Growers can learn a few general underlying principles from these studies.

In a 2017 trial conducted by the USDA Agricultural Resource Service at Stoneville, Mississippi, researchers found that delaying planting from mid-May to mid-June resulted in a yield reduction of 59% compared to only 28% in 2016.

| Year | Planting Date | |

|---|---|---|

| Mid-May | Mid-June | |

| 2016 | 4,969 | 3,581 |

| 2017 | 4,891 | 1,992 |

Source: Burns, USDA-ARS Stonoeville, MS

Though every year is different, growers can expect lower yields when planting is delayed 30-45 days past the optimum planting date in most regions. Heat stress is likely one of the primary reasons for lower yields with late-planted sorghum. High temperatures that occur from 10 days before heading to 10 days after flowering will have a detrimental effect on yield.

Insects are more likely to be an issue with late-planted sorghum. Midge has long been a pest in the southern regions of the U.S., and early planting is one of the integrated pest management strategies for controlling midge. With late planting, growers should scout for midge during flowering and apply an insecticide if needed. Sugarcane aphids are likely to occur earlier in the growth cycle of the sorghum plant at a time when they can cause a severe reduction in yield. Growers should use an insecticide seed treatment, scout fields early and be prepared to apply an insecticide as soon as threshold levels are reached. State extension entomologists have excellent resources available for managing insects in sorghum.

When planting sorghum after a wheat harvest where heavy wheat stubble is present, growers should increase the sorghum seeding rate by 20%. In addition, when applying herbicides, growers should use plenty of water to provide better coverage on emerged weeds and aid in getting pre-emergence herbicides to the soil.

Seeding Rates

In most situations, the sorghum seeding rate should remain the same on a per-acre basis regardless of row spacing. The seeding rate should be based on the yield potential of the field and the environment.

The most common mistake made by new sorghum growers is planting too much seed. Sorghum can compensate for a low population in two ways:

- Tillering: When early-season growing conditions are good, low plant populations will produce additional stalks at the base of the plant, resulting in a higher number of grain heads at harvest.

- Head Flexing: Growers often talk about corn hybrids that can “flex” to produce longer ears and, thus, produce more grain under good conditions. Sorghum plants have a similar ability in that head size is larger at low populations when conditions are favorable.

Research has consistently shown that sorghum plant populations can vary greatly yet produce the same yield. Lower populations will have a higher number of seeds per head, which offsets the higher number of heads that result from a higher seeding rate.

Here are some of the crop advantages of a low seeding rate:

- Better able to withstand short periods of drought.

- Less lodging.

- Typically better head exertion from the leaf whorl, improving harvesting efficiency.

- More efficient plants because more resources go toward producing grain than vegetation i.e., stalks and leaves.

- Possibly less foliar disease due to better air movement between plants.

- Less seed cost.

The seeding rate should be based on the yield goal. The following table provides suggested seeding rates for various yield goals:

| Seeding Rate (seed/acre) | Yield Goal (bu/acre) |

|---|---|

| 30,000 | 60-85 bu |

| 50,000 | 85-135 bu |

| 70,000 | 135-180 bu |

| 90,000 | > 180 bu |

It is especially important that growers use a low seeding rate in sandy soils with little water-holding capacity.

Seeding rates should be based on seeds per acre rather than pounds per acre of seed. Sorghum seed can vary from 12,000 to 18,000 seeds per pound depending on the hybrid. Seed number per pound will be stated on the seed bag tag.

Row Spacing

Row spacing varies by region, but the row spacing for grain sorghum that best fits most environments is 30 inches. A 30-inch row spacing provides a good combination of light interception and enough soil volume to provide stored water during short periods of drought. However, to maximize yield, growers should choose the row spacing that best suits their specific growing conditions.

Wider Rows

In water-limiting environments, wider rows allow sorghum plants to use available water from a larger volume of soil. The wider rows help sorghum to survive and even thrive during short periods of drought. Common row spacing in these environments is 36-40 inches but can go as wide as 60 inches.

Growers also may use wider rows when they expect wet conditions at or around planting time. Under these conditions, a 36-40-inch row spacing may be beneficial, particularly when planted on beds, to allow water to drain away from planted seeds or young sorghum plants following emergence.

In some areas, growers plant sorghum in skip rows, where two 30-40-inch rows are planted and a third row is left unseeded. These row spacings work well when water is limiting, but skip-row spacing prevents the crop from obtaining higher yields if more water becomes available during the season.

Narrower Rows

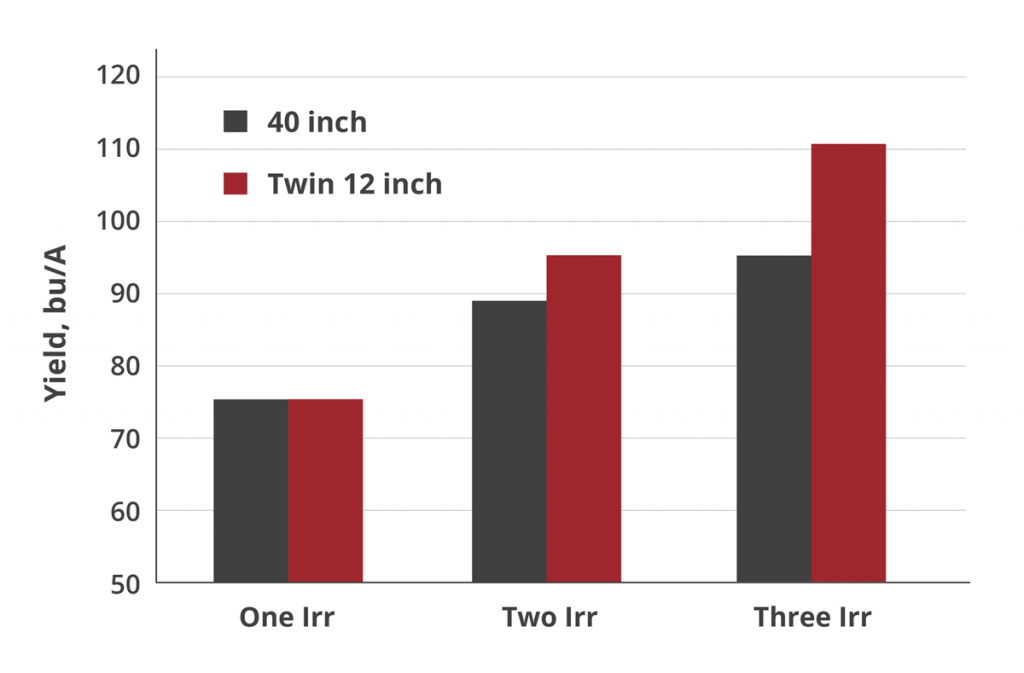

When 36-40-inch rows are used in high-yielding environments, planting twin rows 8-12 inches apart within the 36-40-inch configuration can be advantageous for growers. As shown in Figure 1, research demonstrated that once a 40-inch row approached 90 bushels per acre, the yield was higher when planted in 12-inch twin rows.

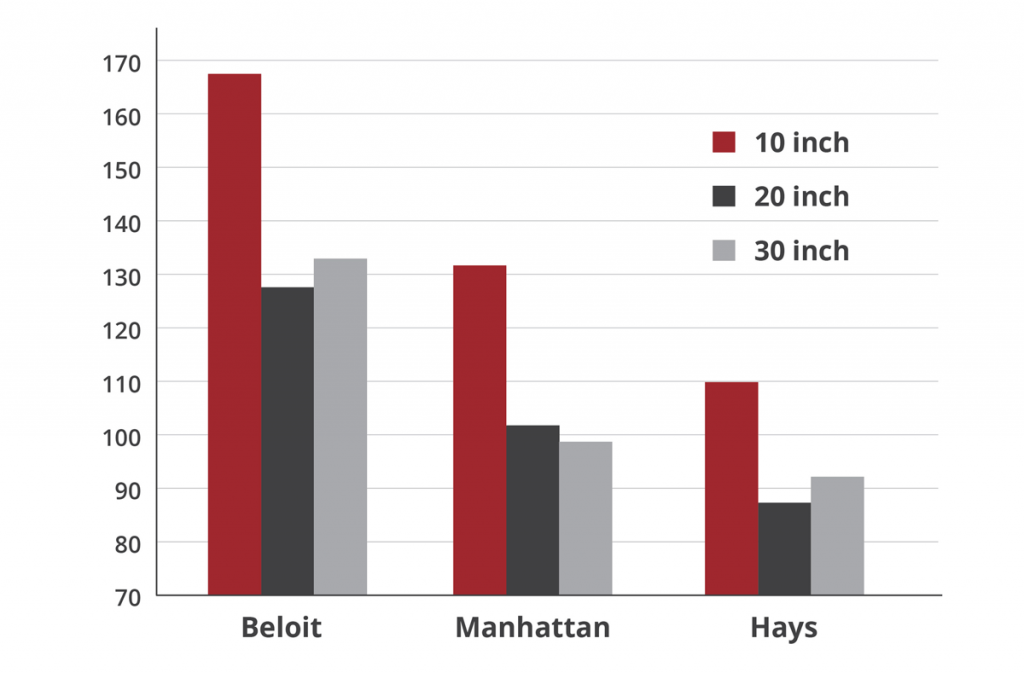

In environments where yield potential is consistently greater than 90-100 bushels per acre, growers should consider a row spacing of fewer than 30 inches. As shown in Figure 2, a study conducted in 2014 at three Kansas locations found that sorghum planted in 10-inch rows yielded 34 bushels per acre more than 30-inch rows in environments where the 30-inch rows yielded 100 bushels per acre or more. At Hays, Kansas, where yield potential was produced less than at the other two research locations, the 10-inch rows yielded 17 bushels per acre more than the 30-inch rows. However, researchers did not consider the difference statistically significant. Other trials have consistently shown no increase in yield when row spacing is less than 30 inches and yield potential is less than 90-100 bushels per acre. Little difference in yield occurred when moving from a 30-inch row to a 20-inch row. To receive a yield benefit from narrow rows, spacing should be no more than 15 inches.

Reduced row spacing also contributes to weed control. Narrow rows canopy quicker, reducing weed emergence and making the sorghum crop more competitive against weeds, especially Palmer amaranth. In a trial conducted by Kansas State University, when researchers did not treat a moderate population of Palmer amaranth, sorghum in 10- and 20-inch rows yielded 86 and 70 bushels per acre, respectively, compared with sorghum in 30-inch rows, which yielded only 50 bushels per acre.